Answering the Alternate Level of Care Challenge: Key Demographic Factors for Policy Considerations

Alternate level of care [ALC] is a serious and costly issue to Canadian health care systems. At any given time, approximately 7500 hospital beds (or between 10-20% of beds) across Canada are occupied by patients who no longer need the level of care provided in hospital after treatment for an acute illness (or those who turn to hospital for admittance due to failed social resources in the community, in which the illness can no longer be managed at home by the individual or their caregivers). ALC patients are awaiting discharge to various alternate forms of care that are not yet available or set up. Such alternate forms of care can include discharge home with or without aid, discharge to a specialized care institution or transfer into a long-term care [LTC]/continuing care facility.[1] However, the majority of patients are waiting for transfer into a LTC facility. Caring for these patients in hospitals costs Canadian health systems up to nine million dollars per day, and three billion dollars per year in mismanaged and wasted resources. ALC thus reduces the effectiveness of our health systems only serving to negatively affect the population in reduced health outcomes.

Patients who are occupying a hospital bed and do not (or no longer) need to be in hospital and receiving the level of resources hospitals are designated for (i.e., higher nursing to patient ratio, specialty physicians available) contribute to inefficient patient flow. Thus, creating hospital gridlock that leads to backlogs in admittance from emergency departments, delays in access to care for surgeries and delayed access to other medical facilities and/or services. ALC patients are often those suffering from complex neurological conditions such as dementia or Parkinson’s disease, behavioural disorders such as Schizophrenia or Psychosis, or chronic diseases such as cancer.

This study examined demographic and patient characteristics of ALC over the 2014-2018 period in Alberta, Ontario and Saskatchewan. The data collected for these provinces along with the existing policy development in each province was examined. Future direction of policy development was discussed to highlight that crucial demographic and patient characteristics must be considered when designing and implementing ALC policies.

Demographic factors (such as age, gender, length of stay [LOS] and patient characteristics (such as clinical categories, reasons for ALC designation, discharge destination) are all factors that can demonstrate patterns or trends in ALC patients. Understanding the demographics and characteristics of ALC patients is critical to ensure policy implementations to address the ALC issue are inclusive.

The following section highlights some key data regarding ALC rates and demographics of ALC patients (obtained from the Canadian Institute for Health Information) from the 2014-2018 period for ALC rates in Alberta, Ontario and Saskatchewan.

Age:

It is evident in the figure below, that the older one is, the more likely they are to be coded as ALC. From this data, ALC rates are highest in those 76 years and older. As Canada’s population ages, and rates of chronic illness are rising, ALC policy development must consider and be adaptable to meet the needs of the aging population and those suffering from chronic diseases such as cancer.

Gender:[2]

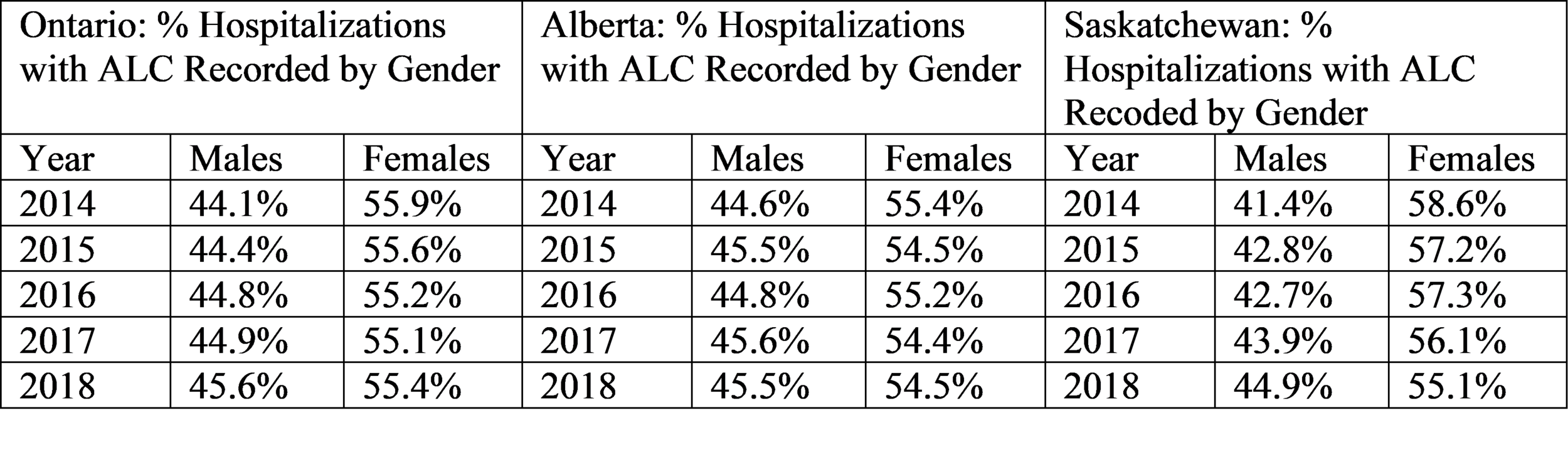

The data in the tables below illustrate that women are more likely to be coded as ALC than men. This is evident across all provinces for the entire period examined. Policies must consider what potential supports may be needed for those who are coded as ALC that may be different for women than men.

Rate of ALC Hospitalization and Length of Stay:

Overall, while Ontario exhibits a stable rate of hospitalizations with ALC recorded, Alberta and Saskatchewan face a rise in the percentage of hospitalizations with ALC recorded.

Length of Stay (Total and ALC)

Analysis of ALC Length of Stay [LOS] as a percentage of total [TLOS] in Figure 7 demonstrates that Alberta has the highest lengths of stay in both total and ALC LOS. Analysis of the change in percentage of ALC LOS as a percentage of total LOS can highlight the need for stronger, or more consistent coding procedures, as well as stronger discharge procedures or transition processes once a patient receives the ALC code.

Analysis of LOS by gender and age as illustrated in the figures below, reveals that men exhibit longer ALC length of stays. Such potential reasoning[3] may include potential greater instance of behavioural disorders or illnesses in men that a LTC facility might not be equipped to manage, and thus patients may need transfer to more specialized care. Additionally, men might have less caregiver support and require greater dependency on the systems supports.

It is critical for further research to better understand why men experience such longer LOS to best create ALC policy that acknowledges and is adaptable to the different ways gender contributes to the strain on health systems created by ALC.

Major Clinical Category [MCC]:

When admitted to hospital patients are classified into a major clinical category [MCC] that denote what part of the body (organ/system) patient is receiving treatment for or is diagnosed for. The following table lists the MCC’s used for this study as well as the figures for each province across the 2014-2018 period.

Of note is the high frequency of ALC patients categorized under category 19: Trauma from Injected Poisons or Toxic Effects from Drugs. This signifies a large need for greater policy and stronger community and social supports for those suffering from substance abuse. Alberta has a much higher rate of MCC in category 17: Mental Diseases and Disorders, indicating a critical need for stronger mental health supports and policies within the province that will help to alleviate and potentially avoid ALC hospitalizations.

Discharge Disposition

The majority of ALC patients are waiting for discharge to a LTC facility. The following data illustrates discharge disposition across all three provinces over the 2014 – 2018 period. Of note, while coding categories changed in 2018, transfer to a LTC facility remains a prominent discharge disposition among ALC patients. This category ‘splits’ into two separate categories in 2018, discharge to a facility without extra supports, and discharge to a facility categorized as assisted living (such as discharge to memory/dementia specific units).

Discharge to LTC is notably a key factor in the ALC issue and any policy and/or procedures developed must understand the interconnected nature of ALC patients and LTC space.

However, simply increasing LTC capacity by building more facilities is not a long-term feasible option to addressing ALC as it is hard to predict the future needs of the populace. Increasing LTC capacity does not necessarily reduce the ALC issue if it cannot meet the continuing increases in demand. Building more LTC, is thus a short-term, or ‘band-aid’ solution to a larger systemic patient flow problem.

Conclusion

Any policies and/or procedures developed and implemented to address ALC must be adaptable to the changing needs of the population to be able to address specific needs, factors, or demographics that can and may face high instances of ALC at any given time. Age, gender, clinical category, and discharge disposition are some of the key factors that tie into ALC and contribute to the strain ALC then places on health care systems. ALC is a costly issue that leads to mismanaged and wasted resources, lower health outcomes, and healthcare inefficiency. With an aging population facing greater instances of chronic illness, it becomes critical for health systems to find ways to combat the strain ALC creates.

[1] This paper uses the term long-term care [LTC], however different health regions have various terms for such facilities including continuing care, assisted living, nursing home, etc.

[2] This study uses the term gender, however, the data obtained from the Canadian Institute of Health Information denotes gender by the sex terms male and female. For consistency purposes, this study refers to gender as the social construct of gender, but the sex terms male and female are used.

[3] These example reasonings are hypothetical and not fact. Further research needs to be conducted to truly understand the scope of the on average longer lengths of stay for men.

About the Author: Stephanie Durante was born and raised in Calgary, Alberta. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in sociology from Mount Royal University and her master’s degree in Public Policy from the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy. This piece provides a synopsis of her master’s research project ‘The Demography and Policies of Alternate Levels of Care: A Selection of Canadian Case Studies.’

The author can be reached at: https://www.linkedin.com/in/stephanie-durante-7a0b671b0/